Photography has always fascinated me. My dad had an old Agfa camera which clicked lovely black and white photographs, which I fell in love with. Those photographs are still a treasured part of my memories, even though the world has moved on to color photography and digital techniques.

Growing up, it was not always easy to take photographs because of the costs involved in procuring the film and then getting them developed. So most of our photos were taken only for the purpose of documenting major events like birthdays and travel. It was rare for us to take pictures for the fun of it.

It was not until the advent of mobile phones and their cameras that I could actually work on my photography. Even then, it was more of the practical aspects rather than the theory of color photography that pulled me. So, it was a delight to read a bit about the origins of photography and to discover some William Eggleston photos.

William Eggleston, the father of color photography, grew up with his grandparents in the small city of Sumner, Mississippi. The youngster played music, drew, and was introduced to photography, which his grandfather practiced as a hobby. Even though the grandfather had his own darkroom and furnished his grandson with a simple camera, Eggleston quickly lost interest.

I believe the rich small city life was the basis for his unique view of color photography.

Eggleston’s interest in photography reawakened when he went to University and his friend persuaded him to purchase a 35 mm camera. He took some courses on photography and began developing his own prints.

He was very much impressed by The Decisive Moment by Henri Cartier-Bresson, which he obtained in1959. Eggleston was impressed by the quality of the prints in the gravure process, and he took a serious look at the photography of Henri Cartier-Bresson.

A Riot of Colors

Eggleston began photographing in color in the mid-60s. After a few unsuccessful attempts with lighting, he eventually mastered the technical difficulties and quickly achieved satisfactory results. For Eggleston, color not only contributed to a better description of the subject but also changed the emotional perception in the pictures.

Before William Eggleston burst onto the scene, the art of photography was mainly restricted to black and white images clicked by masters such as Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. Color photography was mainly restricted to billboard advertisements and ads in print media.

So when William Eggleston showcased his color photographs at The Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1976, the resistance was very severe. Some critics even called it Vulgar to display color photographs as art!

Eggleston photographed in the Mississippi Delta, in his immediate surroundings, with which he had been familiar since his childhood. Not unlike a family album, the pictures showed relatives, friends, animals, suburbs, houses, interiors, cars, and streets. At first glance, they were bound to everyday life and its objects. But upon careful observation, the photographs went far beyond pure description.

At the time, the common processes for color slides did not produce satisfactory prints. In the catalog of a color lab, Eggleston discovered the dye-transfer process, the most expensive print from a slide that the laboratory offered, because it could be produced only by hand. This involved a technique developed by Kodak in the 40s, in which the subject was transferred to paper support in a succession of three-color prints. The end result was a very color-stable print, with which, in contrast to conventional color prints, individual colors could be changed or intensified without influencing the complementary color.

Until the advent of modern digital photo developing, which now permits this type of manipulation without major difficulty, this was the only procedure that photographers had for controlling the individual elements in the coloring of their works. This enabled them to arrive at an artistically based presentation using the depiction of visible phenomena through the medium of color photography, for the color was able to produce its psychological effect.

Eggleston had discovered the decisive technique for his artistic concept, and after seeing the first results, he immediately decided to use dye-transfer prints for his exhibitions. With the help of Walter Hopps, the first portfolio of dye-transfer prints bearing the title “14 Pictures” was published by the Washington gallerist Harry Lunn. With this, Eggleston found a form in which to sell his pictures in a limited edition.

Walter Hopps and John Gossage helped select the subjects for this folder, for Eggleston couldn’t make up his mind about certain pictures. “I don’t have any favorites. Every picture is equal but different.”

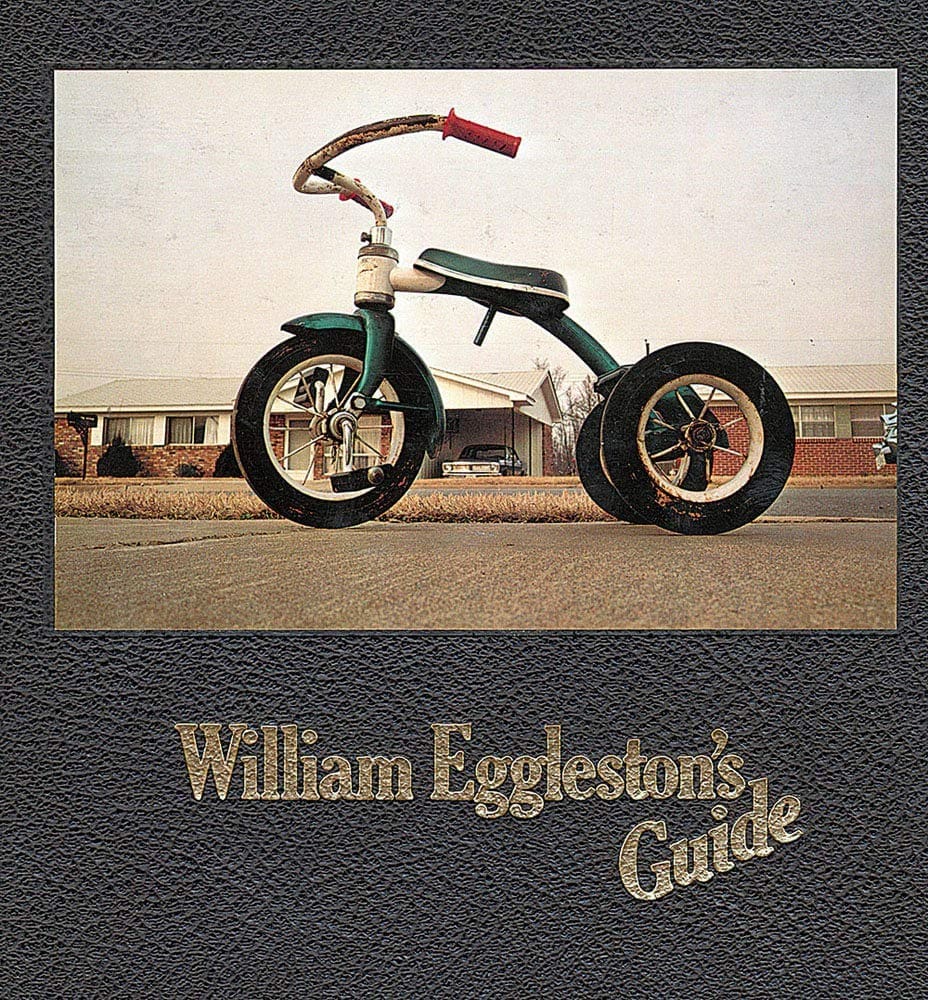

Often the photos were taken from unconventional perspectives. Eggleston photographed a tricycle, which was selected as the title picture for his first book called “Guide”, as he lay on the floor, and it suggested the unfettered view that a child has of an object, which in play can take on multiple meanings. The picture transports this openness of meaning and transposes observers back into a momentary feeling of their own childhood.

A monochrome color photograph of a red ceiling became an icon for Eggleston’s work; its effect was described as: “In the photograph of the ceiling, for example, which skews your vision unusually upward in the room, as if you were seeing with the eye of a fly drawn to the swelling lightbulb, the field of red has an emotional weight — it is though the ceiling was bleeding. here, color reinforces the visual structure’s reference to the Confederate flag — metaphorically a field of blood.”

In discussions of this subject, a poster visible at the lower right edge of the photos is often overlooked. Using pictograms it assigns illustrated positions for sexual intercourse to certain constellations. The connection between the color red — and all the psychological implications associated with it — and sexuality gives the picture further possibilities for interpretation.

The Fascinating World of Color Photography

It still astonishes me that there could have been resistance to something as natural as color photography. The photographs of William Eggleston show how color photographs can be liberating to mind, body, and soul.

I need to spend more time reading about these greats of photography and how their mind processes their surroundings.

thanx for this inspirational article love from deekshaarya