It’s the century of the brown man and the yellow man, and God save everybody else…

Proclaims our shady protagonist as he slips on his shades and turns away from a crowd gathered to greet the Chinese Premier on his visit to India. Set in 2007 India, amid the Internet Boom in the country and touching amply on the many problems that have plagued Indian society for decades, starkly contrasting them with how the urban elite live, India fast rising to be a global economic power, and skimming over lightly with impish humor on the Chinese interest and investment in Indian startups to tell the story of a once-in-a-generation entrepreneur, is the Ramin Bahrani’s film adaptation of Arvind Adiga’s, The White Tiger.

The Man-Booker Award-Winning novel, The White Tiger, has been on my to-read list for many years now with me laying eyes on it as far back as 2009 in my school library, but for some reason or the other, never bring myself to actually read it. Although I did get to purchase it a few months ago, the announcement of the film coaxed me to put it off until after I watched it and for all it’s worth, I think it was a good choice…

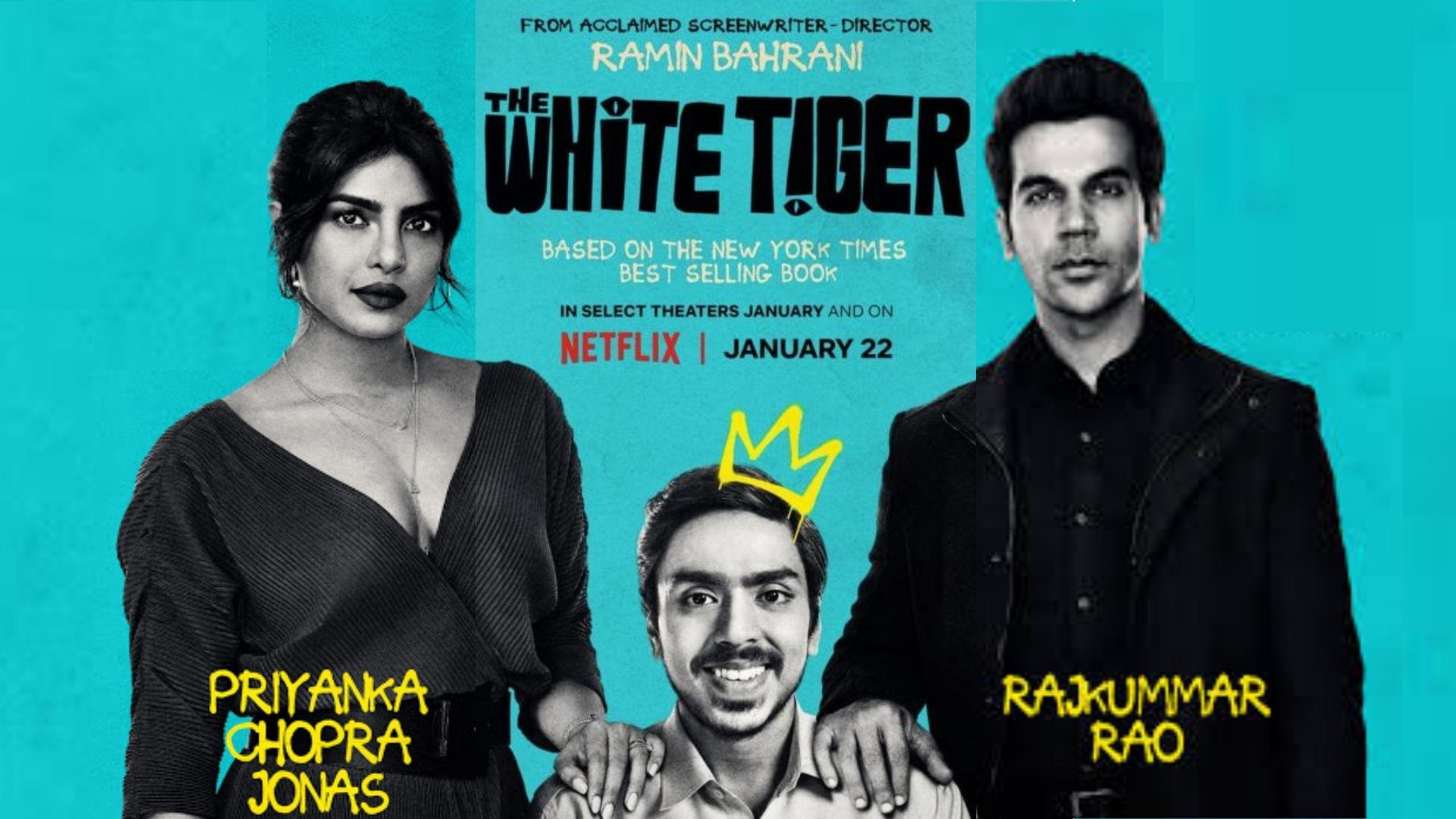

Helmed by one of the finest directors of our time and with steller, nuanced performances put on by the main cast, this is a home run for Hollywood’s fascination for India that seems to be getting films right, finally. Although not without its fault with atrociously bad accents, both Indian and the supposed ‘Indian-American’ and pandering too much to certain stereotypes whilst keeping the West-Influenced Messiah complex written into characters, it’s a huge step up from some of the earlier films set in India we have gotten so far.

The dusty sepia tones of Extraction, as well as the overtly colorful frames of the Marigold Hotel films, are replaced by a color palette more akin to what we’d normally come to expect from India.

The White Tiger jumps back and forth in time with more emphasis on the how rather than the what. As a matter of fact, the opening frames feature Chopra Jonas accompanied by Rao and Gourav driving viciously past a Gandhi statue, a cow on the road, and a homeless family with the horns blaring, before slamming the brakes too late and (maybe?) hitting a child, gives away the turn in the story. In case the viewer was still unsure that the film was set in India, this setting confirms it beyond a shadow of a doubt.

The stark contrasts and the dichotomy of Indian and by extension human character and behavior ring hard and true in many aspects of this film. The rich and their disdain for the poor. The poor and their refusal of denial anyone rich is good resigning themselves to their wretched fate. And the US returned employers who talk about emancipation but turn out to be all the same when faced and forced into adversity.

As the narrator and protagonist, Balram aptly puts it, there are but 2 castes in India. The one with big bellies and the other with small bellies. The characters, right from Balram’s grandmother, Kusum to his employers; the ragtag bunch of servants that live in the gulags below the palatial hotel to the conniving politician whose story from rags to riches mirrors Balram’s own, are representations of India painted to a tee in this masterfully crafted pseudo-reality.

The true entrepreneur who took his first ticket to Bangalore and the luxury of opportunity that Ashok fails to fathom, putting off his dream for want of preparation and the wild ride from Laxmangarh through Delhi and to Bangalore is one written with gut-wrenching realism ingrained throughout.

Balram played with effortless charm by Adarsh Gourav, is made to realize his place early on and his strong desire to break out of the life set for him by society, chaining him down with one shackle after another, takes him to Ashok (Rajkummar Rao) and Pinky (Priyanka Chopra Jonas), a US returned couple set out to change India.

Rao puts up a solid performance as we have come to expect from him torn between his liberal values and the mistreatment of the neeche-jaat wale by the people around him and Chopra Jonas, also the executive producer of the film shines through and through as Pinky, a US-born NRI who can’t seem to wrap her head around India. We live the story through Balram’s eyes, the wretched state the villagers are in, the luxuries his employers enjoy and their attitudes that change and morph through the story.

We see Ashok, who keeps calling Balram, his friend suddenly lash out in anger shouting at his driver and wishing he went to jail. We see Balram, the meek, master pleasing, Country Mouse transform into the ruthless White Tiger, breaking out of his destined rooster-coop with mocking indignation over the course of the 2-hour runtime.

The supporting cast puts up strong performances, bogged down only by choppy uneven dialogue with English shoehorned into places where it has no place being despite the bilingual billing. Vijay Maurya is phenomenal as the burly big brother nicknamed The Mongoose and Mahesh Manjrekar as his father, the landlord plays his part well.

While it is by no means an eye-opener, it is one that gives a strong commentary on how India is as a country and the disparity its citizens live in. Each character is a case study on its own and all put together, they show us. The film strays clear from many stereotypes but still falls prey to many, but with the original author rooting it firmly in India’s status quo, it doesn’t quite turn into an outsider’s idea of India, but it’s far from what it could potentially have been if done right!

The White Tiger is streaming world-wide on Netflix

Be the first to comment