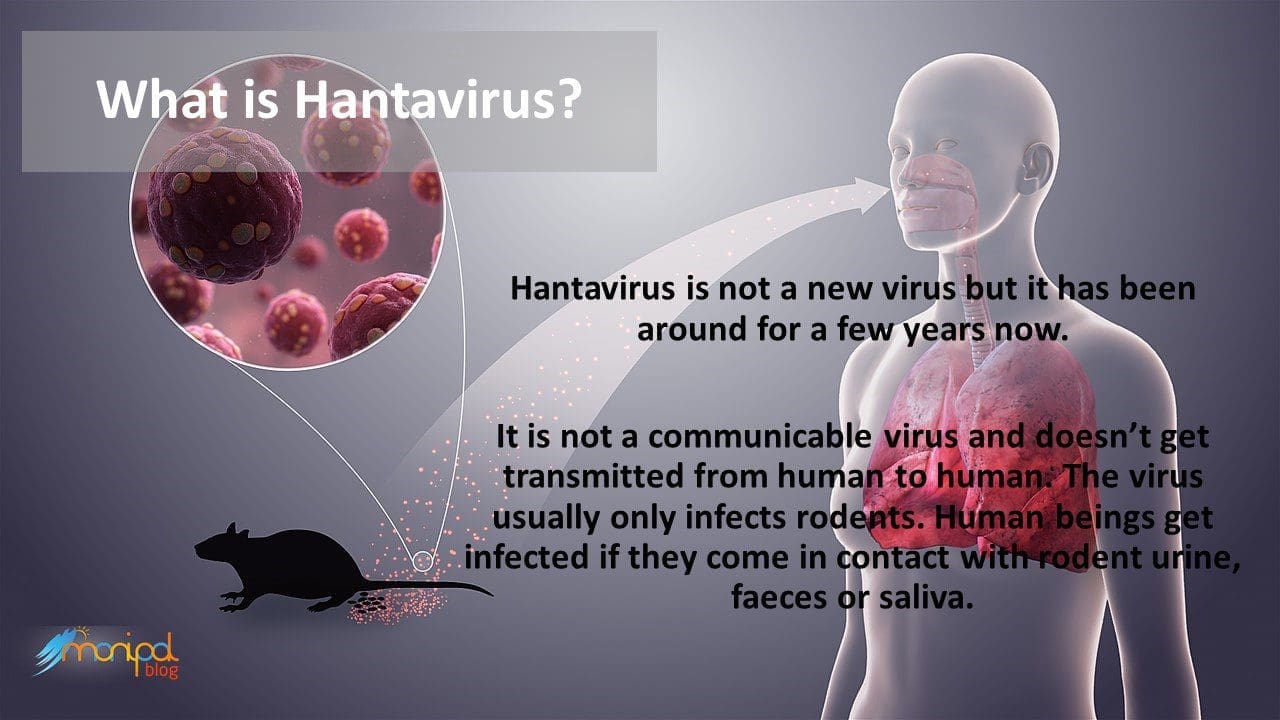

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is creating panic across the world, and the recent news of a Hantavirus infection in China created even more hysteria. The hantavirus is an older and known virus. Here is what we know about it.

Hantavirus safety is something you should take seriously.

If you live in the Americas, you should know about Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS), an infectious respiratory disease caused by the Hantavirus. The Hantavirus is a Biosafety Level 4 pathogen that you can probably find in your own back yard. Without prompt care, HPS is typically fatal, and nearly one-half of all hantavirus-infected individuals have died.

Fortunately, HPS is a rare disease, but it can affect anyone, and it should be acknowledged for its hazards. HPS is very simple to prevent: merely knowing a few critical things about the hantavirus and its methods of contagion can drastically reduce your risks of ever contracting the disease.

What is hantavirus?

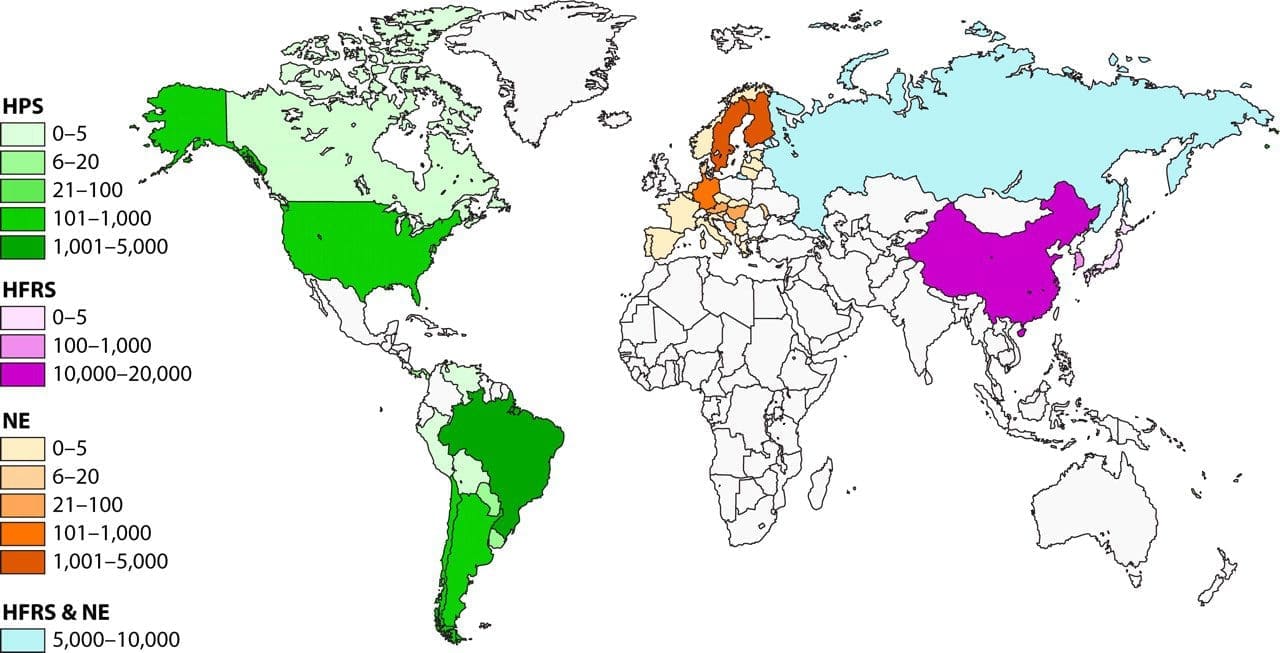

The “hantavirus” belongs to a group of RNA viruses belonging to the family of Bunyaviridae. Depending on its nature, the virus may cause either hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS), hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) or Neuroencephalitis. The HFRS-causing hantaviruses are endemic to East Asia (In this case China), while HPS-causing hantaviruses are endemic to the New World. Neuroencephelitis is more commonly seen among the European and Scandinavian countries. But like all viruses, their distributions are only constrained by the range of their natural hosts.

The natural host of the hantavirus appears to be rodents, which are thus considered vectors for both HPS and HFRS. In the United States, the hantavirus is typically carried by the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) and the cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus). It can also be found in other rodent hosts, such as the marsh rice rat (Oryzomys palustris) and the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus), so other carriers may exist.

What is the history of the hantavirus?

The hantavirus was originally discovered in Asia, during the Korean War. Technically, it was discovered vicariously, through the discovery of the disease it caused: hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS). The actual virus wasn’t isolated until 20 years later, in 1976; it was discovered in a striped field mouse that was trapped near the Hantaan River in Korea. This prototype virus was thusly christened the Hantaan Virus. This virus was eventually classified under its own genus, “hantavirus”, when others forms were discovered in rodents throughout Asia, even extending into Eastern Europe and Scandinavia.

Americans had no reason to fear the hantavirus until mid-May of 1993 when several healthy young members of the Navajo Nation in New Mexico died within a short period of time. Their cause of death was a mystery, enigmatically described by health officials as “unexplained adult respiratory distress syndrome” (ARDS). This cluster of peculiar, unexplained deaths caught the attention of the world, prompting a research endeavour of remarkable haste. The effort involved numerous health agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Indian Health Service (IHS), the University of New Mexico, the Navajo Nation Public Health Center, the New Mexico State Department of Health, and the Office of the Medical Investigator (OMI).

On June 3, as the death toll of the Four Corners epidemic reached twelve, researchers made their critical discovery: this infectious form of ARDS created antibodies that were also produced by the hantavirus, even though no known forms of hantavirus produced respiratory distress, or were believed to exist in North America. While many researchers were sceptical of this claim, the identification turned out to be correct; this alone enabled health professionals to accurately diagnose cases of the disease before conditions became extreme, and it helped epidemiologists determine the virus’ natural hosts with relative ease.

The Four Corners outbreak occurred because of unusual environmental conditions: a warm winter and rainy spring allowed for an exceptionally large rodent population. The region experienced a tenfold increase in the numbers of deer mice from the year before. This population explosion, in turn, exacerbated the spread of the disease. Later that year, the virus itself was given a name: Muerto Canyon Virus, which was eventually changed to Sin Nombre virus. The disease was thusly called Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome.

How do people contract HPS?

Humans don’t usually contract HPS directly from rodents. Rodents shed hantavirus particles in their saliva, urine and droppings. Humans usually contract HPS by inhaling particles that are infected with the hantavirus.

HPS is an airborne infectious disease. The virus becomes airborne when the particles dry out and get stirred into the air (especially from sweeping a floor or shaking a rug). Humans then inhale these particles, which leads to the infection.

Other possible methods of contracting HPS include: (a) being bitten by a rodent that is carrying the hantavirus, (b) eating food or drinking water that has been exposed to a hantavirus carrier, or (c) bringing hantavirus-infected particles or droplets into contact with your nose, eyes, or mouth (e.g. licking your hands).

Ticks, fleas, and other biting insects have not been found to transmit HPS from rodents to humans. In fact, no other animals (apart from the carrier rodents) are believed to be directly involved in HPS transmission to humans. However, it is possible for domestic dogs and cats to bring infected rodents into contact with humans.

It is generally believed that humans cannot spread HPS to other human beings, but cases from an HPS outbreak in Argentina (in late 1996) suggest that this may be a possibility. At any rate, human-to-human transmission is considered the least-likely method of contracting the disease, especially in the United States.

What conditions usually lead to contracting HPS?

Since HPS is not considered a highly infectious disease, people usually contract HPS from long-term exposure. If rodents can be found in your home or workplace, you may be at risk for contracting HPS.

Since transmission usually occurs through inhalation, it is easiest for a human being to contract HPS within a contained environment, where the virus-infected particles are not thoroughly dispersed. Being in a small house, a crawl space, or a barn where rodents can be found poses elevated risks for contracting HPS.

The environments that provide the greatest risk are unoccupied buildings, such as an abandoned house, a cabin, or the toolshed in your back yard. Rodents can thrive in such places, especially in cold weather. The gathering dust will only increase the infectiousness of the disease.

A very common scenario for contracting HPS is cleaning out a dirty shed: if the shed has been a long-standing home to any carrier rodents, then sweeping the floor will aerosolize the virus particles and make their inhalation much more likely.

Travelling to a place where the hantavirus is known to occur is not considered a risk factor. Camping, hiking, and other outdoor activities also pose insubstantial risks, especially if steps are taken to reduce rodent contact.

Can HPS be fatal?

Absolutely. Untreated cases of HPS are almost always fatal. However, if you can get yourself treated for HPS before the disease progresses to acute respiratory distress, then your chances of surviving are greatly increased. Thanks to improved methods of diagnosis, care, and a greater HPS awareness within the medical community, the mortality rate of HPS has rapidly decreased over the past few years.

What are the symptoms of HPS?

The very first symptoms can occur anywhere between five days and three weeks after infection. They almost always include fever, fatigue, and aching muscles (usually in the back, shoulders, and/or thighs). Other early symptoms may include headaches, dizziness, chills, and abdominal discomfort (such as vomiting, nausea, and/or diarrhoea).

These early symptoms are very difficult to distinguish, and as such, they are usually overlooked. In fact, these symptoms are frequently described as “flu-like”, because they indicate that the body’s immune system is kicking in to defend itself against viral infection, flu or otherwise. Most people experience these symptoms at least once a year, and HPS will almost never be diagnosed at this point.

(Conversely, rashes, sore throats, and earaches are not typical symptoms of HPS. These symptoms are sometimes used diagnostically to determine when a hantavirus infection is unlikely. Also, HFRS will lead to haemorrhage and severe kidney dysfunction, which HPS does not.)

HPS starts to distinguish itself in its later symptoms, which usually occur between three to five days later. These pronounced symptoms include coughing and shortness of breath. This is known as the “cardiopulmonary phase” of the disease, where the body reacts as the lungs start to fill up with fluid. From here, the disease progresses very rapidly; the shortness of breath leads to acute respiratory distress, often within 24 hours.

Breathing will become extremely laboured and difficult, and in many cases, it will eventually become impossible for the victim to breathe unassisted. The heart rate will also slow down considerably. If the victim is not receiving medical assistance during this phase of the disease, they will likely die.

The primary cause of death will be excessive proteinaceous fluid in the lungs. The fluid, essentially plasma, is leaked from capillaries into the lungs’ air sacs. Autopsies of HPS victims have found that their lungs were so severely fluid-filled, that they weighed twice as much as expected. However, death is frequently associated with shock and heart failure instead of “drowning”; the body’s response to the trauma is actually more damaging than the trauma itself.

If someone survives the cardiopulmonary phase of the disease, they usually recover very rapidly. Sometimes a recovering HPS patient can have kidney difficulties, such as excessive urination (“polyuria”), but usually convalesce quickly. During the course of the disease, if damage happens to occur to the lungs or lung vasculature, then the patient may experience minor respiratory difficulty after recovery.

What should I do if I suspect that I have HPS?

Seek medical attention immediately. Most HPS victims who receive prompt medical attention are likely to survive the infection. (However, the overall mortality rate is still near 50%, so even immediate medical attention will not guarantee recovery.)

Haste is a very important consideration with fighting HPS. The disease can become acute very rapidly; people have died within hours of suspecting that they were even sick.

How is HPS treated?

HPS is a viral infection; if a severe viral infection cannot be prevented by a vaccine, then it can only be controlled with “aggressive supportive care”, where the patient is provided continued medical assistance and (hopefully) kept alive long enough for their body to develop antibody resistance. There is no specific treatment, cure, or vaccine for hantavirus infection.

In the case of HPS, the patient will usually receive antibiotics initially, until the diagnosis of HPS is certain. Once HPS is proven, the patient will be transferred to an intensive-care unit, where they are carefully monitored for fluid balance, electrolyte balance, and blood pressure.

During the onset of the cardiopulmonary phase, the patient may need to be hooked up to a ventilator, which will hopefully keep them breathing.

Be the first to comment