24th October 2017 was a hesitant night for many academicians as a seemingly harmless Facebook post went viral. An unheralded post on a social media platform had made public a list of sexual offenders. Fifty-eight unapologetic men were named, some of whom had breached the very ideals of morality they preached. Raya Sarkar in her post had brought to the fore, a seething era of mistreatment in the institutions students revere. In the wake of the Harry Weinstein scandal, this was another blow to the veil of feminism adopted by many luminaries.

The Facebook spreadsheet though was just the tip of an impending disaster. Patience with predatory men had been wearing incredibly thin. In a desperate attempt at securing justice, the spreadsheet seemed to undermine the institutionalized laws and jurisprudence. But it also highlighted the precarious situation in our academic institutions. The fact that random women across the country would rather trust a stranger from the internet instead of placing faith in our judicial system questioned the very fabric of our constitution.

Sexual harassment has been a rarely documented prevalence in almost all our institutions. Hidden beneath layers of bureaucracy this issue never saw the light of the day before women like Raya Sarkar, stood up to voice their displeasure. It is because the ‘red tape bureaucracy’ failed to provide necessary redressal. Those students took to naming and shaming predators anonymously in a flimsy document.

While the nature of the actions that may be construed as harassment can vary wildly, it is still necessary to define the boundaries and limitations within which educational/workplace relationships need to function. The vague nature of such accusations adds to the uncertainty. The concept of sexual harassment and abuse depends on the prevalent societal norms up to a varying degree. This leads to an unfortunate amount of abstractness to the allegations and the victim’s suffering. Yet organizations have taken the efforts necessary to define the issue and consequently form laws.

The Ministry of Women and Child Development passed the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act in December 2013. The POSH Act states that any of the following shall constitute sexual harassment:

- Physical contact and advances

- Demand or request for sexual favors

- Making sexually colored remarks

- Showing pornography.

- Any other unwanted physical, verbal, or non-verbal conduct of sexual nature.

The act does not end here. It has further broadened the scope of the term and also included similar other offenses under its umbrella. Due to the precarious nature of such crimes, the definition has been made wide enough to include all sorts of possible sexual offenses either in implication or in a direct manner. The implied behavior depends on the interpretation of the person. It is, therefore, necessary to read between the lines, especially in cases of verbal misdemeanor.

Quid pro quo sexual harassment occurs when an academic or employment decision is based on whether the student or employee submits to sexual demands. When it is explicitly stated or implied that the student must comply with sexual favors demanded entry into a university program or activity then it can qualify as quid pro quo sexual harassment.

Hostile sexual harassment occurs when unwanted sexual advances create a threatening, intimidating, or abusive learning or working environment that adversely affects the performance of the victim and prevents him/her from taking part in any university program. It also occurs when the victim is unable to take full advantage of the benefits offered by the program due to an unwelcome environment.

Statistics show that many colleges violate these guidelines. Colleges are yet to form an ICC for the redressal of such complaints. If the ICC exists then it is rarely a democratically elected body. It continues to be within the influence of the administration undermining the veracity of the committee. Most students are not even aware of the location of the ICC in their college. They lack basic knowledge of the rules to file an official complaint with the ICC. The committee members are not sensitized towards the issue and lack the experience and delicacy required to handle such cases. They indulge in victim shaming blaming which further alienates the sufferer.

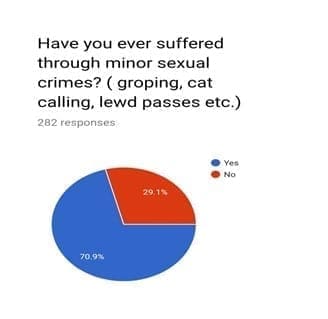

Sexual harassment is rampant across the country in various forms. 70.9% of the participants claimed to have been sexually assaulted in some form. The incidents varied from grievous forms of sexual assault such as physical abuse to catcalling and verbal pauses.

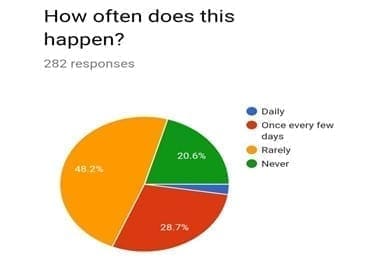

28.7% reported having been subjected to sexual harassment once every few days. Another 3.4 % claimed that it occurred every day. Even if it occurred rarely, it did in a way that left them with very slim chances to tell the respective authority about it.

Even though a majority of the participants had at some point in their life faced sexual abuse, most of them failed to complain to the authorities. 91.1% of the females had not reported their perpetrators.

62.8% had not even mentioned the incident to their peers or family members. Most of the respondents (90.8%) wished to be associated with a platform that worked to spread awareness and raise voices against this menace. A 107 respondents (37.9% ) claimed that sexual harassment happened on campus, while the rest blamed clubs/pubs (52.5% ), public transport (77.7% ) and other (40.4%) locales.

While 53.8% of females claimed to know about the constitutional provisions regarding sexual harassment mandated by the government, only 38.5% were aware of the presence of the Internal Complaints Committee in their college. Out of the 107 participants who had suffered sexual abuse on campus, only 6.7% of them had ever filed a complaint. The statistics indicate a chasm between government laws and their proper execution at the college level.

Sometimes, the victim, out of fear for her life, requires anonymity. But the rules are such that anonymous complaints are not allowed. Sometimes, the non – chalance of the victim also keeps her from complaining. Minor sexual crimes are considered “not that big a deal” and part of everyday routine. This mentality further encourages the perpetrator since he has no fear of punishment. He might even indulge in brutal sexual assault such as rape if he is not punished.

All these reasons add up to create an unsafe environment in the college campuses of India. The scale of the issue is unprecedented and urgent remedial action is required from the government, the college administration as well as the women themselves.

Art work by Sana Khanam

Be the first to comment