A few months ago, I was at the airport, picking up luggage and struggling a little during the process, when two kind people stopped to ask me if I was having trouble with my suitcases and if I needed help. At that moment, I thought how kind it was of those people to notice that I was struggling and stop to help. It was only later that I started to question their kindness. Would I have been treated the same way had I not looked the way I did? Would I have been met with the same kindness if I was an overweight middle-aged woman? Maybe not. Honestly, it wouldn’t have been the first time I was treated better because of how I looked. During the end of 10th grade, I had a “glow up.” This was also when I changed schools. It appeared as if all the kind people were in my new school. People suddenly wanted to talk to me and be friends with me. At first, I just thought they were more kind and welcoming than the people in my old school. I only later realized that they were the same. It was just how I appeared that changed.

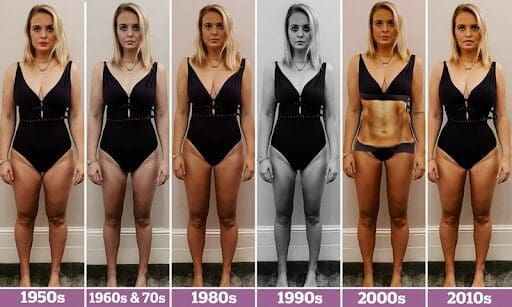

Now, I don’t mean to be all smug and say that I am “pretty” because trust me, I have had too many days when I feel ugly. I realize that “pretty” is a subjective term and that beauty only lies in the eyes of the beholder. However, a lot of “beauty” that lies in the eyes of many beholders is clouded by the traditional cisgender Eurocentric beauty standards of society, and I realize that I might have sometimes gained a few privileges for subjecting to the Eurocentric standards of being thin and fair.

What is a Pretty Privilege?

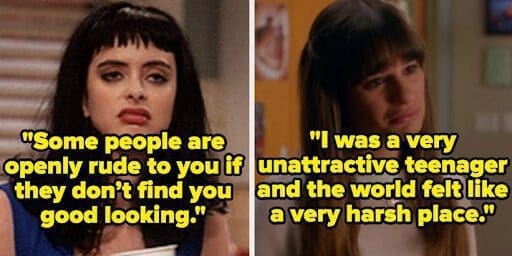

It is a privilege where certain people get the upper hand in society just because of the way they look. The term has gained more visibility now that it is being discussed avidly on TikTok and Instagram reels, and people have started to share their experiences with it. Despite all the proof of its existence, many people don’t seem to acknowledge it. To recognize that certain people might gain benefits just because of their appearance would mean that we are all shallow human beings, and nobody wants to admit that we are all just that shallow. However, acknowledging the existence of pretty privilege is the first step towards unlearning it. Though the standards of being “pretty” have changed drastically over time based on the demographic trends of that period, the privileges that people who uphold those standards gain remain prevalent.

In a 2005 experiment modeling the hiring process, would-be employers were shown photographs of would-be employees, and they were ready to give 10.5% higher salaries to the would-be employees that were deemed more attractive, just by looking at their photographs. This mindset of associating beauty with qualities like kindness, intelligence, competence, and associating unattractiveness with qualities like laziness and incompetence has existed since our childhoods. Even while growing up, we see beautiful Disney princesses portrayed as kind, compassionate, brave, ambitious, while all the Disney villains who are shown as ugly and scary possess qualities like greediness, unreliability, deceitfulness. Therefore, we start to associate prettiness with all the positive attributes and unattractiveness with negative characteristics from an early age.

Why does Pretty Privilege exist today?

Since the dawn of humanity, we have learned to be kind to those things that don’t seem threatening. This used to be a survival tactic. However, we don’t live in an age where we are required to make fire using stones anymore. So why does pretty privilege still exist today?

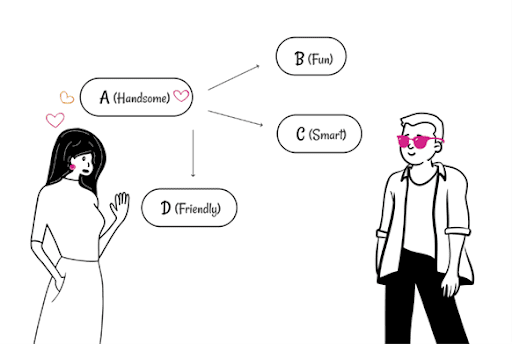

In the early 1920s, an American psychologist, Edward Thorndike, coined the terms “halo effect” and “horn effect” on noticing how people who are deemed more attractive tend to be perceived as competent and successful. We are all guilty of making quick judgments about people before even getting to know them. There is a reason why we give so much importance to first impressions. The halo effect suggests that people tend to assume a person’s entire character in a positive light based on their one redeeming characteristic. For example, say we are meeting someone for the first time, and our first impression of the person is that they are “conventionally pretty,” we immediately assume that they must also be intelligent, friendly, and fun; therefore, judging the entire character of a person positively based on one positive quality. The opposite of this is the horn effect, which suggests that we tend to judge a person’s entire character negatively based on one negative attribute. A well-known example of this is overweight people being stereotyped as lazy and irresponsible.

These unfair judgments we make based on prevailing biases fuel the existence of pretty privilege to a degree where attractiveness could even pay off in the marketplace. It can even affect hiring decisions since most recruitments are based solely on first impressions. Attractive people are also considered more successful. A study at Rice University revealed that subordinates viewed attractive bosses as more competent than unattractive bosses even if both had the same managing style.

The dark side of pretty privilege: How is it dangerous?

Since this is a privilege given to us by society, it can be taken away just as quickly when they move on to the “next pretty thing.” Some of the prettiest people on earth are also the most insecure because they have to think about how they look every minute of every day, which can get very toxic.

It gets scarier when pretty privilege can also affect our decision on whether a defendant is guilty or not. An experiment even reported that jurors were more likely to convict unattractive suspects than attractive ones.

Ted Bundy, a notorious killer who killed and assaulted at least thirty women before he was caught, is the extent to which pretty privilege can get dangerous. You’d think, how could anyone admire a person as horrible as him? But apparently, half of America adored him. He had his own “Bundy effect,” where women would flock near his courtroom during his trials to catch a glimpse of him. They were fascinated by him. Most women didn’t believe he “looked” like the kind of a person who would do such horrible things. Even the police took so long to get hold of him because he just didn’t “look” like a killer. It took the death of at least thirty women for him to finally get caught.

Although this is the extreme of how dangerous pretty privilege can get, it can also be seen in our everyday lives and significantly affect how we meet new people and form relationships. Maybe we could form healthier and stronger relationships if we asked ourselves whether we really connected with a person, or did we just find them attractive and hold ourselves accountable every time we catch ourselves giving an unfair advantage to someone for being pretty.

About the Author: Ishita Jain is a first-year student at Manipal Institute of Communication.

A deep sense of respect for the person who wrote this article. Reading this article really tempts me to know about what runs in this writer’s mind that this person could come out with such a beautiful article that hits the right nerve in a person’s mind. I feel so lost in this article right now that I don’t really know how to appreciate the writer.

This article forced me to get under my sister’s shoes and imagine what she will be going through every day and what each and every woman will be going through on a daily basis.

Looking forward to reading more articles for this writer.